When studying Bach’s music, I feel it would be a great help if I knew more about the mindset that produced these masterpieces. I think some clue may be found in looking onto Martin Luther’s philosophy of music, because Bach seems to have held his Lutheran faith very close to his heart and mind.

Luther’s philosophy of music as I understand it, goes something like this:

-

The very essence of God is revealed in and through the musical proportions: “But thou hast ordered all things by measure and number and weight” (Wisdom of Solomon)

-

Music not only mirrors the order of the created universe through its own numerical order but can positively affect individuals by audibly “putting them in touch” with the greater order of the Creation (God)

-

Music makes man receptive to the word of God, and lends emphasis and potency to the message

-

Through music the invisible becomes audible. Therefore, its role is to praise God and edify humanity

-

Music is a gift from God - a sermon in sound

Dietrich Bartel (‘Musica Poetica’ University of Nebraska Press, 1997) extrapolates further thus: [In this period] the human desire to participate in musical activity is not so much a need for self-expression, as the humanists would have it, as it is a longing for and a reflection of a relationship with the Creator. Music can therefore be used in the struggle against melancholy depression and powers of darkness. For Lutheran composers, unlike the Italians, the musical composition, like the sermon, was the “living voice of the Gospel”. And like the preacher, the composer was to use any artistic means necessary to convince his listeners. For example rhetoric. The role of Lutheran music was therefore pedagogical.

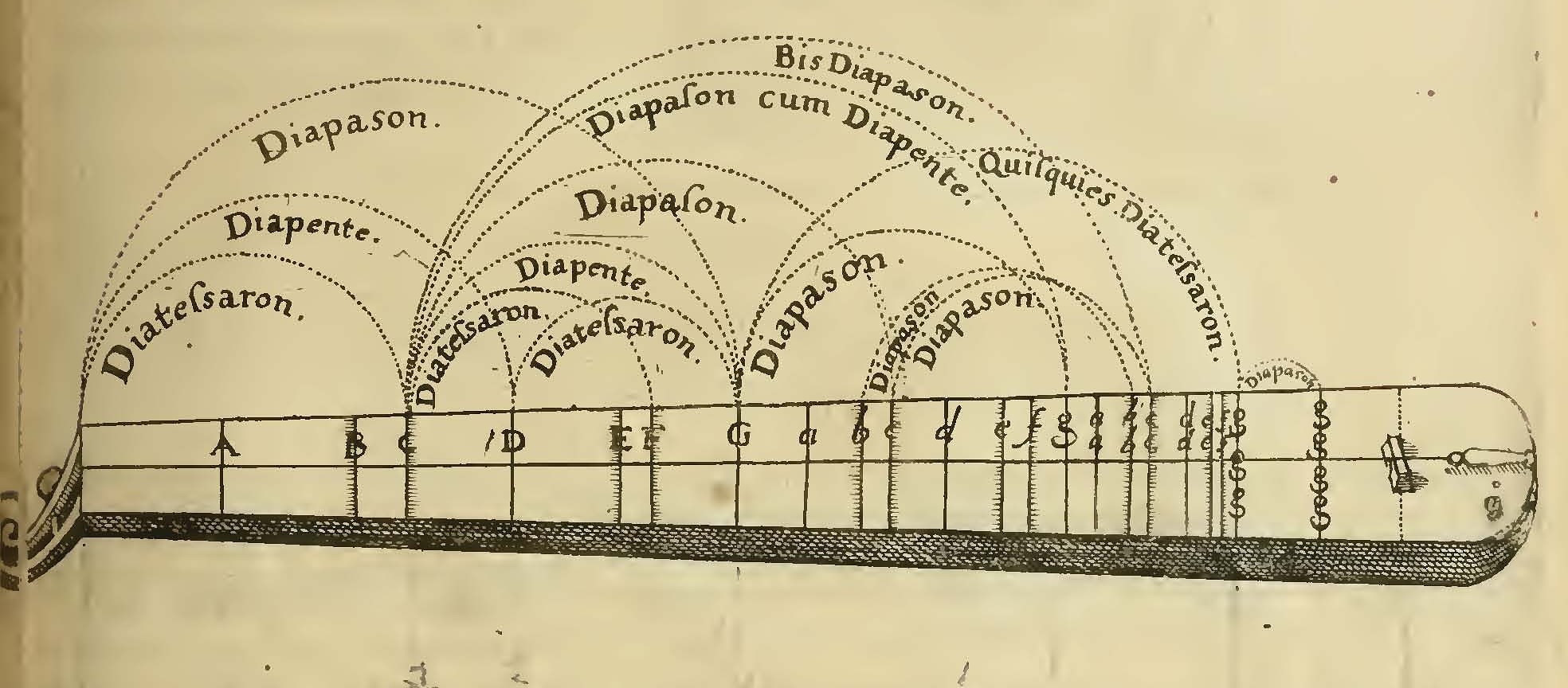

Luther’s theology of music talks about the musical proportions. These are based on the simple theory of the monochord - used since medieval times. So, if a taut piece of string is stopped half way the two halves will have a proportion of 1:1 and will be a unison. If stopped one third of the way along the proportion will be 1:2, and the interval created will be an octave, and so on.

A medieval illustration of a monocord, showing the different pitches/intervals resulting from stopping the string at different lengths.

In summary:

- Unison: (C) 1:1 Octave (C -c )

- 1:2 Fifth (c - g)

- 2:3 Fourth: (g - c')

- 3:4 Major Third (c'- e')

- 4:5 Minor Third (e'- g')

- 5:6 Major Sixth (g - e')

- 3:5 Minor Sixth (e'- c'')

- 5:8 Whole Tone: (c''- d'')

- 8:9 Semitone: (b''- c''') 15:16

Based on this knowledge, the ‘divine origin’ of musical intervals as understood by German Baroque music theorists was like this:

- Unison 1:1 - the starting point of all music/creation. “Perfection = God” (Werckmeister, whose writings were well known to Johann Sebastian Bach)

- 1 = God the Father

- 2 = the Son

- 3, the fifth (2:3) = Holy Spirit

- 1:2 = octave = Father:Son

- 4 = an angelic or heavenly number, representing the angels who fulfill the will of God. As the ‘cosmic’ number, it also represents the four elements, seasons and temperaments. Furthermore, the fourth (3:4) unites the Trinity (1:2:3) with the triad (4:5:6)

- 5 = humanity, (5 senses, 5 appendages). Only when placed within the Divine context, i.e. between the fifth, does humanity find fulfillment. (4:5:6; 4:6 = 2:3)

- The minor third (5:6) remains forlorn on its own without the Divine (see point 4, above)

- 7 does not appear in the proportions, for it is a ‘mysterious’ and ‘holy’ number. It ‘rests’ as God rested on the sabbath, the 7th day of creation.

Bach also encorporated his own name into pieces - presumably that for him had special meaning. For example the third violin sonata in E Major BWV1016:

- B=2, A=1, C=3, H=8.

- 2+1+3+8 = 14

- 2x1x3x8 = 48

- 48 – 14 = 34 (the number of bars in the first movement)

- 48 x 3 (Holy Trinity) = 144 (the number of bars in the second movement)

- 48 + 4 (Angel) = 62 (the number of bars in the third movement not counting the coda)

- 11 (Disciples) x 14 =154 (the number of bars in the last movement)

According to George Buelow, “No other writer of the period regarded music so unequivocally as the end result of God’s work,” a view harmonious with that of Bach. The goal of baroque music therefore became to arouse certain affections (moods) in the listener. Modes or keys were used to express an affection though because the composer and listeners innate temperament both influenced the effectiveness of the keys, rhythm and tempo markings (numerical expressions) are more reliable indications of the affections.

Johann Mattheson (1681 – 1764) a German composer and music theorist amplified this by elaboration on typical baroque dance forms:

- minuet - moderate delight

- gavotte - jubilant joy

- bouree - contentment etc.

Affections on which there is a general consensus:

- Sorrow: harsh or grating intervals and harmonies, syncopated rhythms, intervals far removed from perfection (unison)

- Rage: the same as sorrow, but in a fast tempo

- Joy: consonant, perfect intervals, major key. Rhythm faster, no syncopations, dissonances. Striving towards unision. Tessitura high, brighter sounds.

- Triple time (trinity, perfection).

- Love: longing and joy. Unstable. contrasting effects. Harmonic and melodic material includes both rousing and gentle intervals. Both soft (semitone) and strange intervals. The tempo and rhythm is calm as with the sadder affections.

In the Bach sonatas, the basic affections - Sorrow, Rage, Joy and Love are expressed in abundance. I have also proposed the theory that the moods of some of the sonatas to coincide with special events on the Lutheran calendar - in particular Christmas, and Easter.