In ‘Musica Poetica - Musical-Rhetorical Figures in German Baroque Music’ by Dietrich Bartel (University of Nebraska Press, 1997), Bartel argues convincingly for a unique association between music and rhetoric - a predominantly German Baroque phenomenon - called ‘Musica Poetica’, whereby certain musical ‘figures’ (like motives) represented key affections/moods/words. This became like a local German ‘dialect’ particularly amoung Lutheran cantors, and contributed to the expressive power of music – an important part of Luther’s ‘theology’ of music. This same idea is explored by Judy Tarling in her book „The Weapons of Rhetoric“ (Corda Music, 2004).

Albert Schweizer (1875 – 1965), in his book J.S. Bach preferred to talk about Bach´s „musical language“ and made many insightful correlations between musical imagery used in the Cantatas and Choral preludes and Bach´s purely instrumental work.

This is a huge topic, and anyone seriously interested should read Tarling or Bartel´s books (and there are many others), or delve into Schweizer. But to whet your appetite here are a just few interesting examples of ‘figures’ as refered to by Tarling, Bartel and Schweizer with references to the first two Bach violin sonatas.

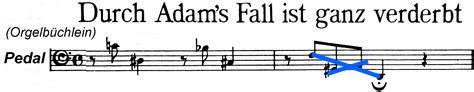

BWV 637 Durch Adam´s Fall from the Orgelbüchlein. A wonderful example of the figure to portray the fall. Schweizer associates wide falling intervals interrupting the natural flow of the phrase, with grief.

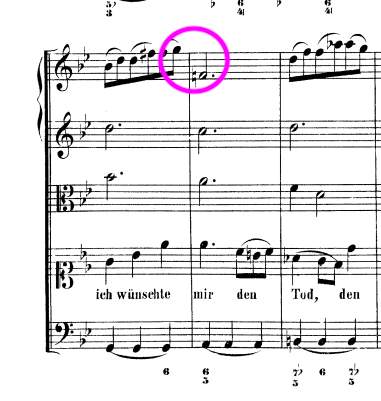

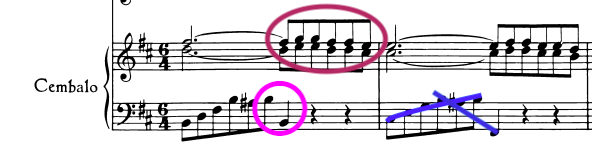

Above: another example of the falling figure from the Cantata BWV 57 which is similar to the opening of the violin sonata BWV1014 (below). Here you can also see the weeping figure (Schweizer „Schmerz figure - red) and the cross (blue)

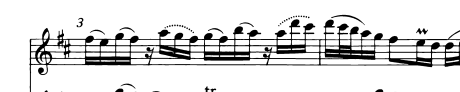

An example of the „auxesis“ figure (called the advancer in English) in the Andante of BWV1014. The climax is reached by degrees built up of falling figures, each rising in tessitura and instensity until the top D is reached:

The opening movement of the second sonata in A major BWV 1015 is a serene movement described by Schweizer as depicting Mary´s Euphoria after the news from the Angel. The frequent use of trills recalls the organ chorale BWV615 „In Dir ist Freude“:

The violin and harpsichord lefthand trilling in unison in the violin sonata BWV1015, Dolce:

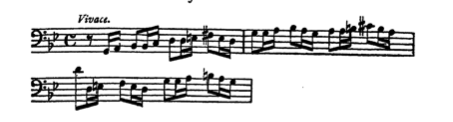

The second movement of the same sonata BWV1015 is dominated by the rhythmic „Freudenmotiv“ (Joy motif):

In the CantataBWV10 „Meine Seele erhebt den Herrn“ it appears thus:

However interesting it may be, I realise that simply finding the figures in the music isn’t enough to make a convincing performance! However, I do believe that this knowledge can help a lot with ideas as to what (and what not!) to do. As Jos Van Imerseel so elegantly puts it:

“The composer provides a good score (by means of harmony, counterpoint, motivic-construction), but the responsibility for its realisation certainly rests with the performer. If this is not the case, if the performer doesn’t understand or even notice all the different types of figures, or if the realisation is insufficient, then these devices will contribute more to boredom than they will attract the listener’s attention.The score is not more than a map, and the doctrine of the figures is no more than an analytical codification of all the possibilities of human expression in music. For without the human element, true music can never exist.”